The Dakota Apartment House

In the 1880s, Rafael Guastavino introduced the Catalan tile vault system to America and singlehandedly transformed the American construction industry.

After Guastavino’s death in 1908, his obituary in the New York Times called him "the architect of New York." The nickname was a reflection of his huge influence on New York city's architecture. By the time his company, the Guastavino Fireproof Construction Company, closed in 1962, it had installed its specialized tile vault system in approximately one thousand buildings across America.

But from the 1930s onwards, there was a move away from the ornate, curvilinear forms of Beaux-Arts architecture, towards the clean, straight lines and functional minimalism of the modernist movement. The Guastavino Company's workload steadily shrank, until facing dwindling commissions and changes in architectural taste, the company closed in 1962.

Guastavino's company's archives, the architectural drawings, correspondence, contracts, photographs, tile samples, and patents, were at risk of being lost to history. These valuable papers and materials were only just saved from a dumpster by George R. Collins, professor of art history at Columbia University.

The archive was donated to Columbia in 1963. As custodian of the archive, Collins, a specialist in Catalan architecture and the work of Antoni Gaudí, preserved, curated, and expanded the archive until it was transferred to Columbia’s Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library in 1988.

Collins actively researched the Guastavino legacy, collecting materials and fragments of vaults from demolition sites, compiling extensive documentation of the company's projects and preserving Guastavino’s unique architectural heritage.

In 1968, he published a seminal academic paper, The Transfer of Thin Masonry Vaulting from Spain to America, reviving scholarly and public interest in Guastavino’s work and saving Guastavino’s work from oblivion

Guastavino in Catalonia

The following section on Guastavino’s early life in Spanish Catalonia, is based on Santiago Huerta’s article on Academia. Edu: Rafael Guastavino and the migration of tile vaulting to North America.

Born in Valencia in 1842, Rafael Guastavino Moreno moved to Barcelona where he studied to become a master builder, Maestro de Obras. While studying, he became fascinated with the possibilities of using tile vaulting in architecture. In his book written in 1892, he described his «illumination» when visiting the grotto of the Monasterio de Piedra:

‘Here, in the “Monasterio de Piedra”, I saw a grotto of immense grandeur, one of the most sublime and extraordinary works of nature (…) The thought entered my mind, while in this immense room, viewing this fall of water, that this entire colossal space was covered by a single piece, forming a solid mass of walls, foundation and roof, and was constructed with no centres or scaffolding, and especially, without the necessity of carrying pieces of heavy stone, and heavy girders or heavy centres ; all being made of particles set one over the other, as nature had laid them (…) This grotto is really a colossal specimen of cohesive construction. Why had we not built using this system?’

While still a student, he became involved in the design and construction of different projects. His first design was for his own house in 1866. Quoting again from his book:

«I tried the first experiment on myself, as a physician might try his own medicine, carrying out my ideas by building a construction four stories in height, with practically no beams, using clay and cement».

His most important work from this era was the Batlló Factory, Can Batlló, an enormous textile factory in Barcelona where Guastavino displayed his mastery as a builder. The construction lasted seven years from 1869 to1875 and established his reputation.

The floors were supported by tile vaults, and the image of the main hall is like a manifesto.

The Loom Room of the textile factory Can Batlló created by Rafael Guastavino.

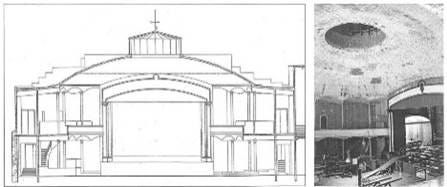

During the next twelve years Guastavino was very active, building apartment houses, factories, warehouses, and the Massa Theatre in Vilassar de Dalt in1880. He covered the theatre auditorium with an extraordinarily thin dome, seventeen meters in diameter, with a rise of three meters, and a thickness of only five centimetres. He used a single shell of flat bricks, plastered on the inside and covered in a layer of cement.

La Massa Theatre, Vilassar de Dalt, Catalonia (1880-81).

In 1876 Guastavino presented some architectural designs for the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. When he received a medal of merit, he decided to emigrate to America:

«The success attained at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition, and the great Chicago fire, which made an impression on all European minds, convinced me that this country (America) was the proper place for the development of the Cohesive System».

Guastavino patented his tiled vaulting system in the United States in 1892 and the following year, published his "Essay on the Theory and History of Cohesive Construction," in which he called his technique the Guastavino Cohesive System, as it relies on the cohesive adhesion of materials rather than gravity to hold the vault together.

Fear of fire

In Chicago, in 1871, a fire razed the town, leaving 100,000 people homeless and 300 dead.

A year later, the Great Boston Fire destroyed sixty-five acres of downtown Boston, including most of the financial district. The fire killed thirty people and destroyed seven hundred and seventy-six buildings and over a thousand businesses. It was one of the most destructive urban fires in American history.

Fire had become a major concern as most structures at the time were made of wood. Many Boston buildings were made of brick and stone, but their wooden mansard roofs and frames were highly flammable.

Architects and builders were looking for a more fireproof way of building. It was a perfect opportunity for Guastavino to demonstrate the quality of his Catalan vaults. They were not only fireproof but were quick to build and cheap.

Guastavino’s early years in New York

Guastavino emigrated from Barcelona to the United States with his youngest son Rafael in 1881. According to Collins, the work he had done in Barcelona before he left made a deep impression on Catalan architects and builders, «his buildings were studied by classes of the School of Architecture».

Rafael Guastavino’s early years in America were not easy.

Guastavino didn’t speak English when he first arrived, and with no money or business connections, he had to prove himself before being accepted by the city's builders.

He took on minor projects and cultivated relationships with leading architects, slowly establishing his reputation and introducing his unique building techniques to American architects and clients, in the hope of obtaining a large commission.

Guastavino spent his first five years in the US studying American construction methods and materials. He talked with architects and builders and published some decorative works in journals. In 1883 he constructed two fireproof apartment houses and the following year, a club and a synagogue.

Before Guastavino’s arrival, most of the vaults and domes in American buildings were false vaults of lath and plaster suspended from hidden timber trussed roofs. It took time for Guastavino to convince American architects and engineers, as well as the local authorities, of the feasibility and safety of his tile vaults.

Those who knew Rafael Guastavino found him to be a brilliant, talented man, energetic and full of enthusiasm. W. Blodgett, who worked closely with Guastavino after 1889, portrayed him as energetic and industrious:

‘Contrary to the general impression as to the Spanish character, I found him an extraordinarily alert and active man, both physically and mentally; in fact, I never met a quicker man in all my experience; a very hard worker day and night himself, he demanded the same kind of service from those associated with him - always industrious and never idling.’

The Arion Club in New York

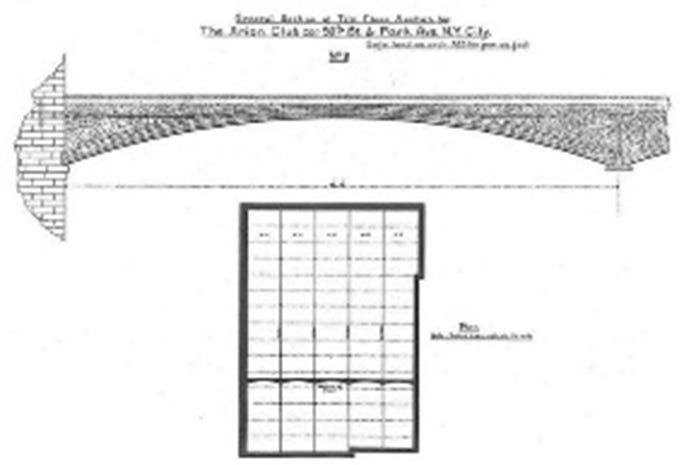

In 1886 Guastavino competed for the design of the Arion Club in New York. He failed to win the full contract but was contracted to build the floor vaults.

The image below shows one of the floor vaults and the floor plan of the Arion Club, constructed by Guastavino between 1886 and 1887, with thin, interlocking, terracotta tiles and layers of mortar.

The floors were robust, fireproof, soundproof and water resistant. The vaults followed the curve of the floor, producing flatter arch profiles with little horizontal thrust on the supporting walls, they were thick but still lightweight and efficient.

Section of a floor vault and floor plan of the Arion Club, constructed by Guastavino in 1886-87.

Guastavino’s Fireproof Construction Company.

Since the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, fire prevention measures had become an essential component of any new construction. One of Guastavino’s first jobs was as a contractor in charge of "fireproof construction" for the luxury Dakota Apartment House.

Guastavino built the Dakota’s floors using the same patented fireproof vaulting technique he had used for the Arion Club. A system that was both fireproof and structurally sound. The floors featured three-foot-thick arched vaults on each of the ten floors between the basement and attic.

The vaults, supported on deep beams of wrought iron, span more than five meters. Hidden iron ties carry the thrust of the arch at the perimeter making each barrel vault strong enough to stand independently. It was a powerful demonstration of Guastavino’s building skills. He was often consulted by architects.

In 1889 Guastavino established his Guastavino Fireproof Construction Company and at the same time he built a ceramics factory to make the specialized thin bricks locally. The ceramics factory became a successful business that made his fortune. In the same period the Guastavino Company recorded twenty-four construction patents. The most important being the ‘volta Catalana.’

Guastavino also began his first big American roofing project in 1889, a collaboration with McKim, Mead and White for the construction of the vaults of the Boston Public Library.

Traditionally Guastavino’s tiled vaults had been plastered after completion, but for the first time, Guastavino left the joints exposed, using the herringbone pattern of the tiles and their joints as a decorative motif. This exposed tile finish then became Guastavino’s signature, transforming his tiled vaults into architectural art.

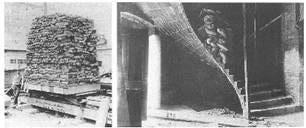

At this time Guastavino made his first tests on small tile arches and vaults to demonstrate that they would safely sustain heavy loads. Around 1900 he made more impressive load tests and in-situ tests to demonstrate the safety of certain elements. The images below provide powerful proof of the enormous strength of Guastavino’s tile vaults.

Load tests made by Guastavino. On the left a specimen vault built in 1901 supporting a massive, heavy load. On the right, an in-situ test of a helical tile-masonry staircase, demonstrating impossible-looking equilibrium and stability.

THE DAKOTA BUILDING the “most famous apartment building in New York City.”

The Dakota building was designed by architect Henry Janeway Hardenbergh, for businessman Edward Cabot Clark, who made his money as co-founder of the Singer Sewing Machine Company.

The design of the building is unusual and has been variously described as German Renaissance Revival, Gothic Revival, or a Renaissance château.

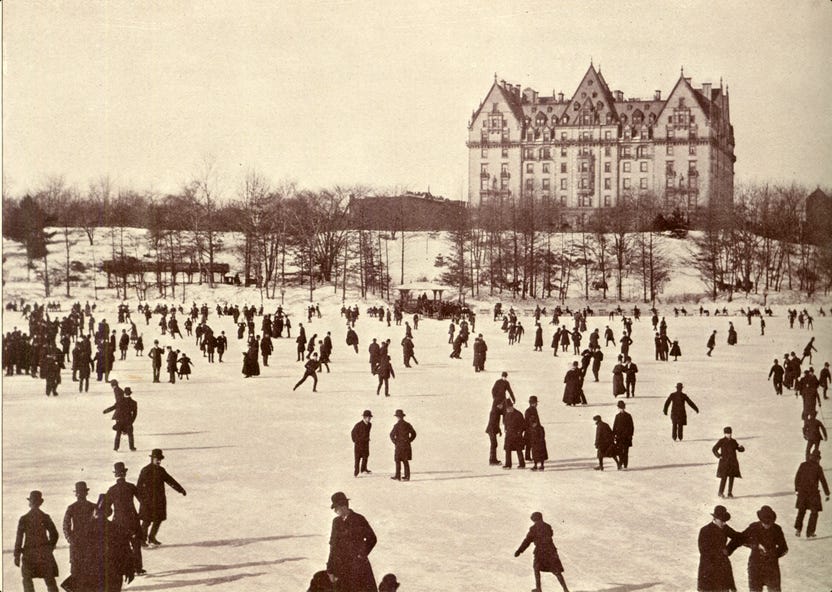

Clark’s plan was to make the West Side of New York as affluent as the East Side. His Dakota building was an ambitious, risky speculation. In 1880 the building site was "in the heart of a squatter's shanty district, where goats and pigs were more frequently encountered than carriages in the muddy streets." Its remote location gained it the nickname of "Clark's Folly." When completed, the building was still surrounded by unpaved streets and vacant lots. But the Dakota was on the edge of Central Park Lake, the area soon became prime property.

Ice skaters in the 1880s on the frozen Central Park Lake in front of The Dakota Apartment House.

Plans submitted to build a "Family Hotel" west of Central Park included fireproof stairways and partitions of "brick or fireproof blocks." The building was like a fortress with three-to-four-foot-thick foundations, iron beams, massive load bearing walls, heavy interior partitions, and double thick floors. When completed in 1884, the building was one of the quietest in the City.

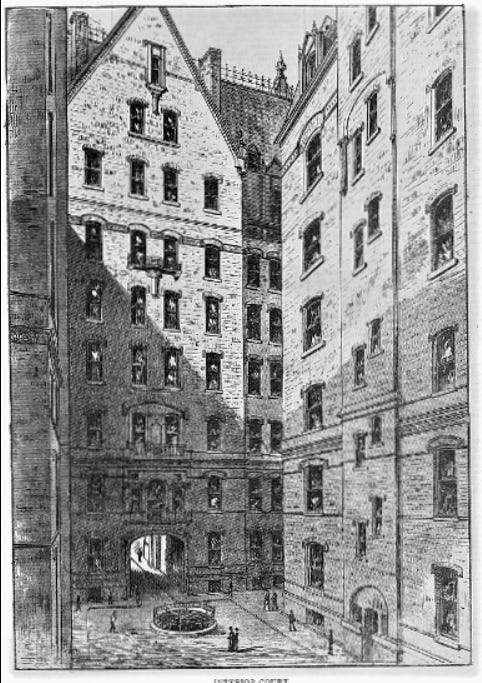

The groin vaulted entrance of the Dakota Apartment House

The luxurious interior of the Dakota apartments with carved wooden fireplace and doorways, and ornate plastered ceilings

Clark’s genius was to recognize that in New York the time was ripe for apartment living. Haussman had transformed Paris in the 1850s, by building uniform, grand apartment buildings that influenced cities across Europe. Apartment living had become the norm in London, Paris, Berlin, and Vienna. But the concept had not yet reached New York.

A detail of the Dakota

Clark offered the wealthy every possible luxury and amenity to entice them away from their fancy townhouses. His apartments were so glamorous that life under a shared roof became as acceptable in Manhattan as in the grand capitals of Europe.

The building was designed to give the residents the utmost in personal privacy. The apartments varied in size. Each apartment had very high ceilings and a unique layout - the smallest apartment had four rooms, while the largest had twenty.

The Dakota came fully equipped with room service, a restaurant, laundry services, a gym, and a housekeeping staff of maids, janitors, chimney sweeps and an elevator with a man to operate it. There were so many housekeeping staff that the top two floors of the Dakota were designed as staff quarters.

Rents might have been high but in exchange the tenants received impeccable service. Maids and porters came in every day to clean out the stoves and fireplaces, removing the ashes and replacing the coal and firewood. Laundry was taken away and returned freshly cleaned and ironed. There was a restaurant on the main floor, styled like an English baronial hall. But if the residents preferred to eat in, meals would be delivered and served by the restaurant staff.

There was a private rooftop promenade with gazebos, pergolas and canopied sunshades, as well as private tennis courts on the adjoining lot.

The Dakota building

The Dakota is a square building built around a central H-shaped courtyard, with an entry in each corner. The building was divided into quadrants, each of which had a staircase and elevator for tenants, and a separate staircase and elevator for the servants. The courtyard provided access to all the apartments and doubled as a light well, providing natural light and ventilation, and hiding the fire escapes required by law.

In the 1880s the 72nd Street entrance served as a porte-cochère - a covered entrance to provide shelter for passengers alighting or disembarking from their carriages. The private inner courtyard was large enough for horse-drawn carriages to turn around after their passengers were dropped off.

The courtyard allowed residents to climb in and out of their carriages in privacy.

"From the ground floor four fine bronze staircases, the metal work beautifully wrought and the walls wainscoted in rare marbles and choice hard woods, and four luxuriously fitted elevators, of the latest and safest construction, afford means of reaching the upper floors."

Clark never saw his vision realized. He died in October 1884, before the Dakota was completed.

Clark’s son Alfred and his descendants managed the building for the following eighty years. Until In 1961, the Dakota's residents bought the ten-storey building from the Clark family and converted it into the housing cooperative still in existence today.

The Dakota tenants

The Dakota is still one of the most desirable addresses in the City of New York. It has been home to many artists, actors, and musicians. Before the Dakota Board considered letting any anyone get a foot in the door, they required a wealth of financial statements, tax records dating back years and a detailed background check.

The Dakota has long been a haven for artists. It has been home to Judy Garland, Lauren Bacall, Leonard Bernstein, Rosemary Clooney, Boris Karloff, and John Lennon and Yoko Ono.

Judy Garland’s apartment

Former Beatle John Lennon and his wife, Yoko Ono, lived in the building. But on December 8, 1980, as Lennon and Ono were approaching the entrance late at night, Mark Chapman, a mentally disturbed fan, fired five bullets from a .38 revolver, hitting Lennon four times in the chest and shoulder. Lennon was rushed to Roosevelt Hospital but was pronounced dead on arrival at the age of forty.

Former Beatle John Lennon and his wife, Yoko Ono in front of the Dakota Apartments

121-131 WEST 78TH STREET – “The red and whites”.

Another of Guastavino’s early projects was a row of houses that he designed and built for the French-born developer, Bernard S. Levy, at 121-131 West 78th Street, between Columbus and Amsterdam Avenues. According to The Record and Guide they were predicted to be “novel in their architecture … a combination of Moorish and Renaissance.''

The row, completed in 1886, is a kaleidoscope of brick Moorish elements, with multiple-centred arches, intricate banding and unusual projecting cornices. After being painted red and white in the 1990s, the row became known locally as "the red and whites.”

Guastavino also designed the brownstone row across the street, at 118-134 West 78th.

No. 129, West 78th Street is the most intact in the row. Much of the original Guastavino detailing remains – the Beaux-Arts-style iron door, the leaded glass transoms, the perforated Moorish-style panels, the cross-hatched patterns on the doors and a stair balustrade with intricate fretwork. The Belle Epoque fireplace, with bronze cresting, female nudes and intricate raised decoration, may also be original.

Guastavino’s successes

In 1892 Rafael Guastavino published an important book to explain his work: ‘Essay on the Theory and History of Cohesive Construction, Applied Especially to the Timbrel Vault’.

Guastavino never relaxed. He was good at self-promotion and took excellent photographs of his construction process and finished buildings. He promoted his Fireproof Construction Company by distributing the photos as advertising leaflets to journals, architects, and builders.

Fortunately, from the mid-1890s his son, Rafael Guastavino Jr, joined the company. Records show the R. Guastavino Company had projects in forty U.S. states, four Canadian provinces, and eleven foreign countries including Cuba, Canada, Mexico and India.

Rafael Guastavino Jr was as industrious as his father. He became a true master of vaulting and ran the company successfully after his father’s death in 1908.

When Rafael Jr. retired in 1943, he sold the company to their business partner and treasurer, Malcolm S. Blodgett, who ran it until its closure in 1962.

______________________________________________________________________

If you wish to receive new articles as they are published, please subscribe to my free Substack elysoun.substack.com. I would love you to share the link and invite your friends and family to subscribe.

If you have read and enjoyed my article, please let me know by clicking on the heart icon below. I would also welcome your comments.

Thank you for reading!